The Complete List of JE Tests

The Complete List of JE Tests

Why Do We Have To Do It?

Because AS 2401 (PCAOB), AU-C 240 (ASB), and ISA 240 (IAASB) say so. Okay, but why should we do it?

Why Should We Do It?

The regulators are using analytics to uncover financial statement fraud. Therefore, we need to use it so we aren’t left at a disadvantage. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has an Audit Quality Model referred to as “RoboCop” that analyzes financial statements within 24 hours of being submitted—to identify potential fraud. Not only are they analyzing the actual numbers, they’re analyzing the text to look for particular phrases, keywords, or linguistic elements used by bad actors to confuse readers on complex issues. The SEC built this analysis based on prior fraudulent filers. So, with each new fraudulent filing, the analysis will become more accurate.

According to Richard Lanza and Scott Gilbert, “The practical reality is that financial statement fraud occurs in 1% of digital transactions, so improved tools for detection are needed beyond manual review. This is an area where more transaction testing using data analysis can provide a superb defense against management override by performing a more extensive search for unusual ledger activity.”

How to Conduct the Analysis

Step 1: Figure out if you have all journal entries

Test the data for completeness by doing a roll forward of all journal entries to the period-end trial balance for each general ledger account.

Phase 2: The tests!

These can be done at the end of each quarter or at the end of the fiscal year. It would take a team of people to do all of these, so add additional tests as you automate the analysis.

- Determine the time between submission and approval of the transactions. Small time differences can indicate that the approver isn’t performing a review with appropriate precision and sensitivity. It might also indicate that the submitter is logging in with the approver’s credentials to circumvent the control.

- To determine how precise management is doing estimates, identify the percentage of journal entries with even amounts at $100, $1,000, $10,000, etc.

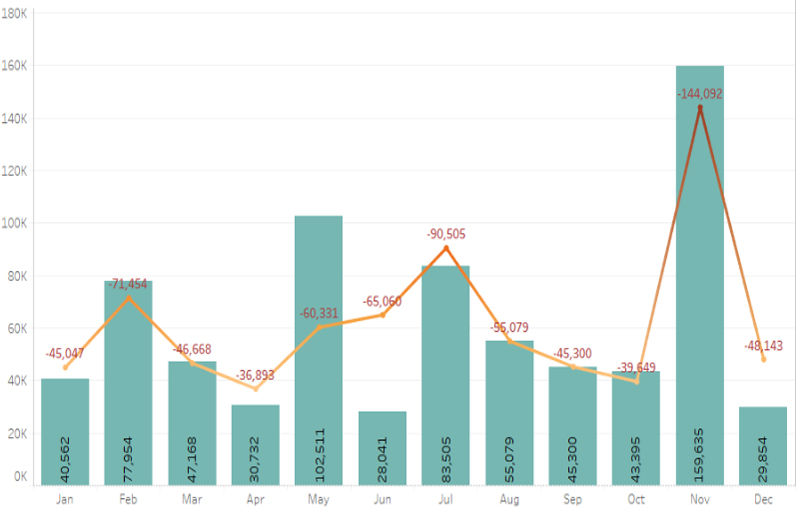

- Do a bar graph with amount and time to identify unusual activity near quarter-end or year-end. Do this for a few years’ worth and see if the unusual patterns are relatively consistent.

- If possible, obtain the IP address of the submitter and the approver to determine if they are the same. The same IP address could identify the submitter circumventing the approval controls.

- Perform a text analysis of the descriptions to identify uncommon words.

- Identify transactions made during typical non-working days (weekends and company holidays).

- Identify transactions that have the words per, error, correct, clear, write off, writeoff, write-off, adjust, fraud, help, reverse, CEO, CFO, fix, correction, restate, or variance.

- Use a scatter-graph on the general ledger accounts (debit and credit amounts separately) and the number of transactions.

- Graph uncommon words over time to see if they show up routinely, at the end of the quarter, or the end of the year.

- Identify manual entries to AR.

- Inquire of management to determine an unreasonable dollar threshold for journal entries. Take the absolute values and identify the line items over the threshold.

- Summarize journal entry credits and debits by day, month and year.

- Identify all fields with any blank entries and understand whether they’re appropriate.

- Identify journal entries where the entry date for one or more line items is greater than ‘x’ number of days before period end.

- Find possible duplicate account entries.

- Identify journal entries that are more than three standard deviations from the average for each general ledger account. Activity greater than three standard deviations are considered outliers.

- Graph uncommon words associated with each submitter and approver to identify trends.

- Summarize debits in revenue and by general ledger account.

- Identify entries made by individuals whose job titles are not indicative of someone that would make journal entries.

- Find gaps in journal entry number sequence.

- Identify journal entries made to suspense accounts and summarize by the person entering them and the related account numbers.

- See who has access to post a journal entry and determine if they are appropriate.

- Similar to the above, but see who has access to approve a journal entry. Then see if anyone has access to both approve and post a journal entry.

- Perform a Benford’s Analysis with two digits.

- Look at journal entries from the prior year that were made right after the fiscal year-end.

- Look for accounts not in the chart of accounts.

- Identify journal entries that are just below the accounting department approval limit. Benford’s Analysis can help with this.

- Extract journal entries to general ledger accounts known to be problematic or complex based on past issues (errors of accounting in journal subsequently corrected by accounting staff or auditors) at the company or the industry in general. Determine journal entries related to the general ledger that have been corrected in the past or investigated by audit.

- Determine if off hour transactions are made by the same employee.

- Calculate unbalanced journal entries.

- Summarize general ledger activity on the amount field (absolute value of debit or credit) to identify the top occurring amounts.

Lastly, combine the results of some of the tests noted above and see which journal entries hit multiple tests. Note which teams you’ve inquired of based on the results and observe any changes in activity. Since they’ll be more aware of what audit is looking for, they’ll look for other ways to throw you off their trail in the event of malicious activity.

This list can be pretty daunting depending on how many of these you’re already running, so if you aren’t doing any journal entry testing then don’t worry. Just pick a few and run with them.